Estuarine crocodile

Crocodylus porosus

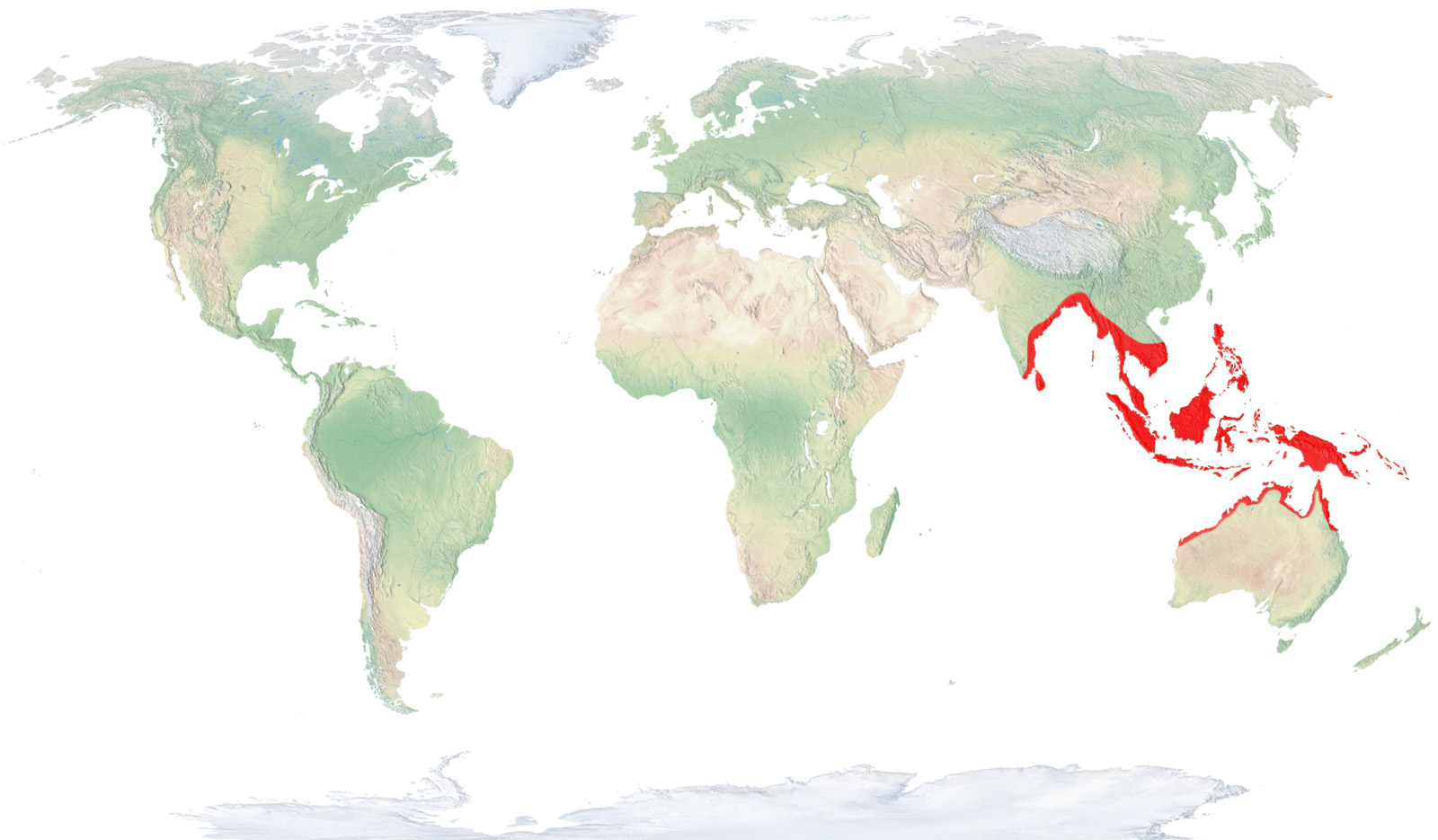

This species can tolerate saltwater extremely well, and is found in estuaries, saltwater marshes and even on the open sea, which is why it is also called the marine and saltwater crocodile. Its area of distribution is extensive in all of Southeast Asia.

The young feed on insects, amphibians, crustaceans and small reptiles, while adults eat all types of vertebrates. This crocodile obtains the largest size of all species, with lengths of six to seven metres and weights of over 1000 kg.

Natural habit

Coasts of India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, northern Australia, New Guinea and small islands of the Pacific.

- Distribution / Resident

- Breeding

- Wintering

- Subspecies

Risk level

- Extint

- Extint in the wild

- Critically endangered

- In Danger

- Vulnerable

- Near threatened

- Minor concern

- Insufficient data

- Not evaluated

Least Concern

Taxonomy

Class

Reptilia

Order

Crocodylia

Family

Crocodylidae

Physical characteristics

500-1200kg

Birth Weight:

3-7m

40-50 years

Biology

Habitat

Fresh water

Social life

Solitary

Feeding

Carnivorous

Reproduction

Gestation

75-100

Days

Baby

40-90 eggs

Biology

Description

This crocodile, with a large head and a very long muzzle, has ridges running from the eye orbits and along the snout. Its armour is not very ossified and a significant trait is the absence of large post-occipital scales. Colouring is highly variable, with four or five black bands that usually disappear on older individuals. The abdomen colour is solid, cream or golden yellow.

Habitat

They live in estuaries, marshes, lakes and saltwater bodies and are sometimes found at open sea.

Feeding

This opportunistic carnivore captures prey when they approach the water to drink. Then the crocodile surprises them, gripping them in its powerful jaws, then dragging them into the water to drown them. The young feed on insects, amphibians and small fish, while adults eat fish, amphibians, eggs, reptiles and mammals, both small and mid-sized. If there is no living prey around, it will also eat carrion. This species kills and devours several people every year.

Reproduction

The breeding period takes place during the wet season, between November and March, when the males defend their territory against other specimens. After mating, the female normally lays 40 to 60 eggs, even though this number can reach 90, in a nest buried underground and made with mud and plant matter. Given that the eggs are laid during the rainy season, the nests must be built at higher areas to prevent their loss from flooding. The female watches over the nest to protect it from predators during incubation and, after the babies hatch, she carries them to the water in her mouth.

The gender is directly related to the temperature of the nest. Males are produced in the range from 30 to 32 degrees centigrade, while females are born if the temperature is higher or lower.

Conduct

This is the largest living reptile in the world, with specimens up to seven metres long and weighing over 1000 kg. It is closely related to the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) and has many similarities to this cousin, including their danger to humans.

This crocodile can be exceptionally agile in the water, with swimming speeds up to 43 km/h and can launch itself up to four metres with a single switch of its tail. It is also quite fast on land, but only for short periods of time.

This crocodile goes into the sea more often than any other, and has been spotted many times at large distances from firm land. A translucent protective membrane over each eye protects it while swimming, so it can see perfectly underwater. It can remain underwater for up to two hours, during which its metabolism slows down and its heartbeat changes, as this animal can direct blood almost exclusively to the life centre—or brain—while submerged,

Status and conservation programs

They have been intensively hunted throughout their area of distribution, because their skin has the highest quality. Thus, they appear to be at the point of extinction in Australia and other regions. However, with rational control of hunting and the establishment of breeding grounds to produce skin, not only has the species been saved, but today it is an abundant animals in certain regions of Australia and New Guinea, where the largest and most aggressive specimens are regularly controlled.