Sacred ibis

The ancient Egyptians worshipped this bird and that is why it has its name. They associated it with the rise in the levels of the River Nile. Strangely enough, nowadays Egypt is the region where fewest of these birds are found.

The characteristic bill of the ibis makes a useful tool for finding invertebrates, amphibians and small reptiles to feed on from the mud in the rivers and wetlands of its natural habitat.

Natural habit

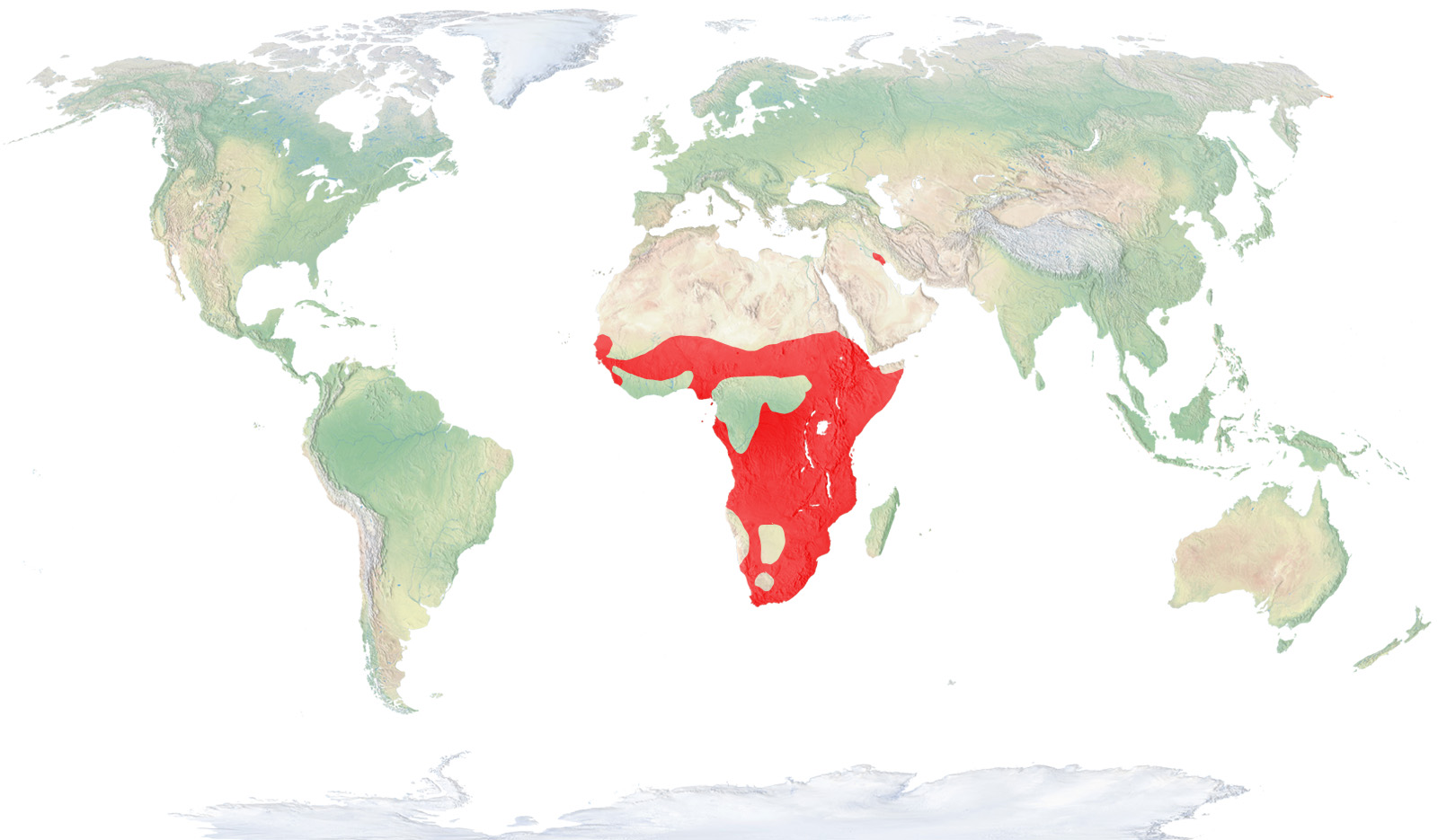

Almost the entire African continent and the island of Madagascar.

- Distribution / Resident

- Breeding

- Wintering

- Subspecies

Risk level

- Extint

- Extint in the wild

- Critically endangered

- In Danger

- Vulnerable

- Near threatened

- Minor concern

- Insufficient data

- Not evaluated

Taxonomy

Physical characteristics

Biology

Reproduction

Biology

The African sacred ibis catches the eye due to its long curved bill and the contrasting white and black colours. Indeed, the head and neck are completely bare of feathers and black, like the legs and bill, contrasting with the plumage of its body, which is white except for the scapular feathers and the tips of the primary feathers, also black.

The name ‘sacred’ is due to the veneration held for this bird by the ancient Egyptians, who associated them with rising levels of the Nile River. Oddly, today Egypt is one of the countries where the ibis is most rare and has totally disappeared from a good part of the Nile River valley.

Dispersed throughout almost all of the continent of Africa and the island of Madagascar, they are commonly seen near rivers, lakes and swamps, seeking food on their shores.

The iconic bill is an extremely useful tool for extracting small insects, crustaceans, molluscs, frogs and small reptiles from the mud.

During the breeding season, which varies depending on the latitude, ibises group into colonies, often in the company of other Ciconiiformes, or wading birds. They build their nests by accruing branches on the tops of trees and thickets or even on the ground. They lay from two to five eggs, which are incubated by both members of the couple for 28 or 29 days.

This species can be totally sedentary when conditions are fitting, although they can also migrate hundreds of kilometres during drought season in specific regions of equatorial Africa.

At present, there are wild populations in different places in Europe, such as France, Italy and the Canary Islands, probably originating from individuals that escaped from captivity.

Although they are practically extinct in some countries like Egypt and face a delicate situation in other places like Madagascar and the Aldabra Islands, they are still quite common in a large part of their area of distribution.